The French under Napoleon ruled Bruges from 1795 until 1814 when the area became part of the Kingdom of the Netherlands. That only lasted until Belgium gained its independence in 1830. French was initially the official language, but Flemish was recognised by the start of the twentieth century. It is the principal language of Brugge and northern Belgium.

Bruges makes a fine character in a novel. The quays, the labyrinth of streets and canals, the Beguinage, churches and belfries, the real and reflected appear simultaneously in the visual and written world. In Rodenbach’s novel, photographs are used to add an extra dimension to this identity.

“Bruges was his dead wife. And his dead wife was Bruges. The two were united in a like destiny. It was Bruges La Morte, the Dead City, entombed in its stone quays, with the arteries of its canals cold once the great pulsing of the sea had ceased beating in them.”

“Bruges was his dead wife. And his dead wife was Bruges. The two were united in a like destiny. It was Bruges La Morte, the Dead City, entombed in its stone quays, with the arteries of its canals cold once the great pulsing of the sea had ceased beating in them.”

Words, image and mood melt into a form of music. Stand anywhere in Bruges and sense the still water of the canals, search for the distant pulsing of the ocean. Look into the depths, and see them stare brazenly back. Hugue is smitten with Jane, the dancer. who, as in a mirror, is a reflection of his late wife. An actress is but a mirror, fashioning the face of your heart’s desire. You have used that mirror and, when you think of it, everyone loves themselves. Narcissus is portrayed, too ardent by far, mesmerised by his own reflection in a pool. So, when Hugue commutes with his wife through a mirror, with whom is he really talking? And when Hugue strangles Jane, his wife’s reflection, who is it that he kills?

On the second evening I dine in a place called the Old Bruges. One side looks onto a little square where the canal turns, the other onto the now quiet Vismarkt. I order Flemish Stew which is a goulash equivalent, and a few steins of beer. Beer is expensive, but it’s strong, with a rich variety available throughout the city. And, I suppose, a certain unreliability of narration may ensue, here or there.

Nearby, a young Australian holds court. I overhear most of the conversation, without committing it to memory all that accurately. It was enjoyable more in the manner of an abstract painting, or a drum solo. The story includes a dwarf and a prostitute. The narrator’s acquaintance prompts, jovially, that the line should read: a dwarf and a prostitute walk into a bar. Who knows where this is heading. Who shall give and who receive? Does someone call them a pink lady and a small one?

The story merges in my head with McDonagh’s narrative In Bruges, wherein Colin Farrell’s character befriends a vertically challenged actor during a Bacchanalian interlude. The dwarf will intervene with devastating and ironic effect in the film’s denouement. Farrell has, after all, killed a small boy, an altar boy, in his botched assignment. This macabre dance with death circles the dizzying spire of Our Lady’s, where love and sacrifice are given expanded meaning. Farrell, no more enamoured of the city, complains he doesn’t ‘want to die in Bruges’.Or perhaps he’s just curious for more.

Later, I am in Delaney’s Bar, seated next to a couple from the nearby Dutch town of Breda, a place I know of vaguely. There was a battle there, long, long ago. It features in a book by Carlos Perez Reverte. They have a festival based on the colour orange, which probably dates back to King Billy. As the dry heat of the day wanes to a cooler humidity. It will rain, says the young man. But when? Oh, give it ten minutes. In his hand, the screen on his phone shows a jagged peak within the next ten minutes. We wait, and it comes to pass. These are the days of miracle and wonder, so it is no surprise that people can capture electricity in their hands and with it arrogate the magic power of prediction. Here was a man with the power of rain in his hands. I asked him could he make it stop, as I was about to make my way home. But he laughed and said that no, he could not.

I sloped off by way of colonnades and the shelter of trees, the cobbles slick with rainwater and electric light. That was when I found myself lost, if you catch my drift. In the giddy valley of cathedral spires and teetering turrets, the alleys threw themselves into ever increasing spirals, farther and farther away. I asked directions of a waiter, who had retreated from the heat of the kitchen for the balm of a well earned smoke. He pointed me back the way I had come. Reluctant to accept this defeat, I returned to where I had spied a sliver of canal slip behind some buildings and took what I judged to be a parallel lane. Dark, deserted, and eminently paranoia inducing, it twisted and turned before curving at last onto Rosenhoedkai. I was no longer lost, but not quite found.

A love struck Romeo sings the streets a serenade,

laying everybody low, with a love song that he’s made,

finds a convenient streetlight, steps out of the shade,

says something like, you and me babe, how about it ,,,

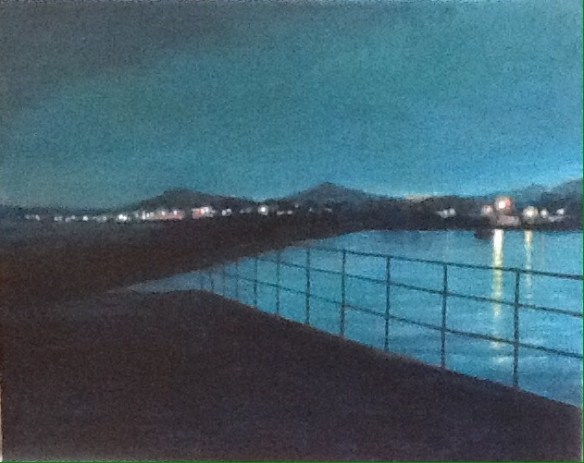

Stars spring from the canal depths. Along the quays, nighttime beckons. I’ve been whistling past the graveyard so that the melody haunts me still. An opera for our age, terse and tunnelling through our formation. Mark Knopfler singing, as an aria should, of love and an Italian girl.

All I do is miss you, and the way we used to be,

all I do is keep the beat and the bad company,

all I do is kiss you, through the bars of a rhyme,

Julie, I’ll do the stars with you, anytime.

The next day I return to the old city walls to complete my semi-circling of the city. The eastern precinct includes the Coupure and the outer canal. This houses larger and more long haul canal craft. You can book canal tours here but the atmosphere is distinctly local and feels remote from the bustling tourist scene at the centre. My camera battery went kaput at the same time, so I’ve only my soul and memory to call upon, which seems about right.

I had intended availing of the Breydelhof’s free bicycle, but these boots are made for wandering, and who knows where they’ll take me. Last night I was lost in Bruges, and today I try for a similar state in daylight. With some success. Crossing old tracks I experience the pleasure of recognition, the uncertain traveller’s concept of home.

Mainly, I was distracted by my own meditations. As evening waxed, I had been thinking of the possibility of finding God in a bar, as Joan Osborne might have speculated.

If God was one of us

just a stranger on the bus, just a slob like one of us,

trying to make his way home.

I must find my way back up to heaven all alone. God might be in the next bar, which is pulsing unsteadily across the Vismarkt. Slouched there at the corner peering into the shrinking muniscus of his pint, apart from the crowd and not exactly pleased to see me. Catching him there, I could ply him with drink, insist on answers to those great questions: why are we born to suffer and die, where might I find the Golden Fountainhead. It must be here somewhere, in this city of chocolate, waffles, and fine beers.

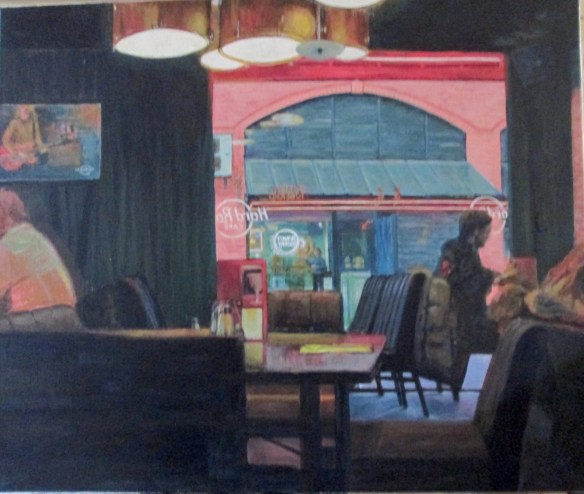

There is an Argentine restaurant on Flammingstraat, north of the Market Square. They serve steak, grilled to perfection. Within the darkwood interior, evening sunlight intrudes in a solid shaft, a slant off the horizontal. We are all reduced to silhouettes. It is the perfect condition for the near slumber of after dinner. My stein of beer still froths. I look down the room towards the window. Other diners dance mellowly in the glare while theatrical gauchos flit in attendance or ennuie. I am briefly blinded by the glare, abruptly occluded by my waiter. We share an acknowledgement, and as he moves aside, I see at last, the Golden Fountainhead.