At the end of Grassmarket the road divides. Straight on and you pass under the bridges that buttress the Old Town. Candlemaker Row slopes upward to join George IV Bridge with the wall of Greyfriars Churchyard along one side. The Grey Friars themselves were Franciscans whose monastery was dissolved in 1560 as Scotland was gripped by the Reformation. The cemetery was a replacement for the St Giles Cathedral churchyard up on the Royal Mile. It was a place of free assembly and The Covenanters signed the National Covenant here in 1638. This asserted the primacy of the Scottish Presbyterian Church but their revolt was soon defeated in the Battle of Bothwell Bridge. Following the battle, four hundred prisoners were held in a section of the churchyard, and it became known as the Covenanters Prison.

Most famous of the kirkyard’s former residents is a wee dog. Greyfriars Bobby. A Skye Terrier, he belonged to a nightwatchman with the city police, John Gray. When Gray died in 1858, it is said that Bobby, his watchdog, kept watch at the graveside until its own death fourteen years later. By this time he had become well known, to the extent that Edinburgh’s Lord Provost, William Chambers had the dog licensed and collared. A year after Bobby died, English philanthropist, Lady Angela Burdett-Coutts was so touched by the story that she had a statue erected in is memory. Outside the gates you’ll find the granite fountain surmounted by a lifesize bronze statue of Bobby.

The legend has grown. I saw the Disney film back in the early sixties. This was based on Eleanor Atkinson’s novel of 1912 and has a different version of events. Here, John Gray is a farmer who comes to Edinburgh and dies. A major character is Mr John Traill, of Trail’s Temperance Coffee House, who in real life claimed Jock and Bobby were regular visitors. As the coffee house was opened four years after Gray’s death, it may be something of a shaggy dog story. A more recent film in 2005 controversially starred a West Highland Terrier playing Bobby, an example of cultural appropriation. The Temperance Coffee House was located outside the gates, and is now, thankfully a bar. Greyfriars Bobby’s Bar is an old style pub, with outside tables to catch the midday sun

Around the corner on Forrest Road is Sandy Bell’s, another pub on the Rankin Rebus Pub Crawl. This is a folk bar with evening sessions featuring Irish and Scottish traditional music. It’s a century old and was first known as the Forrest Hill. Blossoming in the folk heyday of the sixties, Barbara Dickson, Billy Connolly and Gerry Rafferty are amongst its alumni. In the 80s a landlord installed a puggie or slot machine, bane of British pubs, but the regulars delivered an ultimatum, either it goes or we go, and it lasted all of a day. Sandy Bell’s became the official name in the nineties, as that’s what everyone called it, dating back to the twenties when the pub was owned by a Mrs Bell.

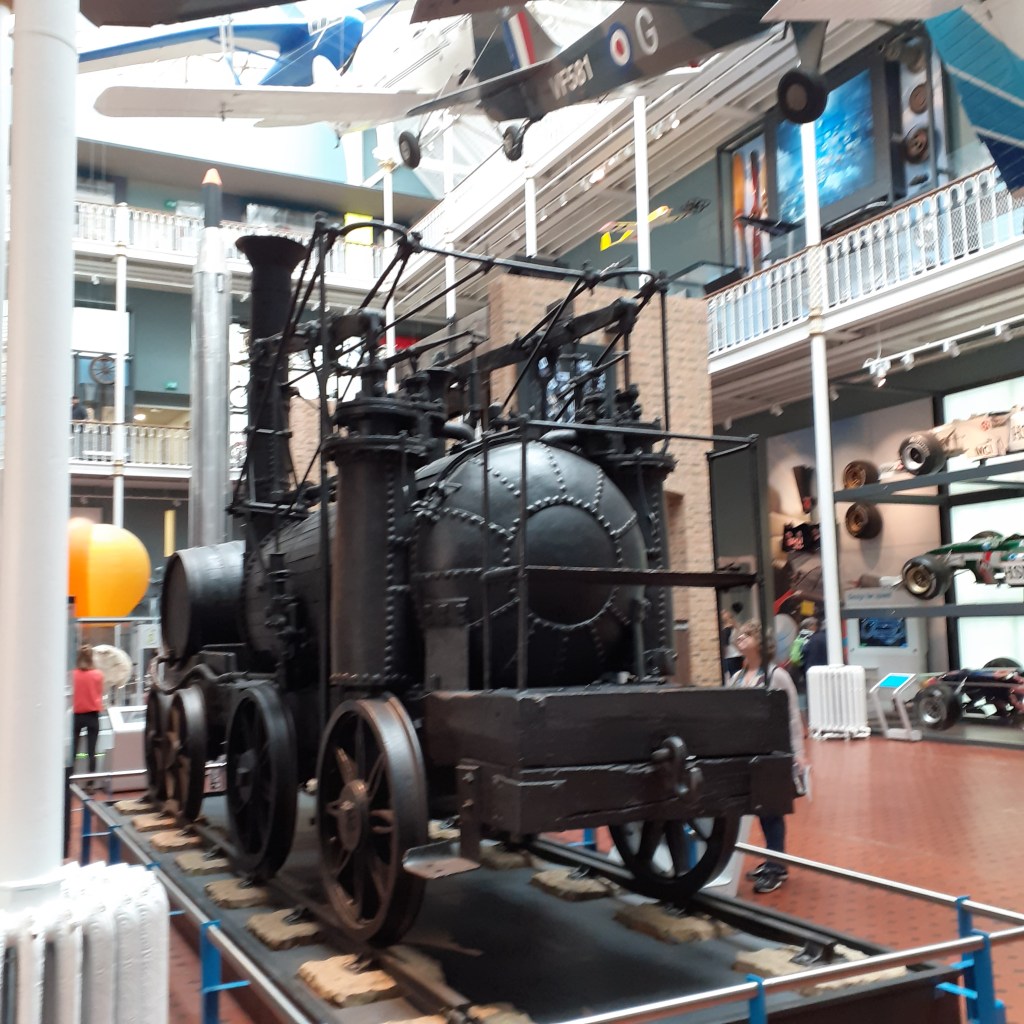

Across the street is the Scottish Museum. This is two buildings. The Royal Museum was built in the 1860s and houses displays of industry, science, technology and natural history. The modern building from 1998 is a formidable and concrete slab in the Le Corbusier style, which paradoxically concentrates on history and antiquities. Admission is free. The old building has that Great Exhibition air to it; the Grand Gallery of cast iron and light was inspired by the Crystal Palace.

The Discoveries Gallery features the world of adventure and invention.You can meet Dolly the Sheep. Born in 1996, she was the first mammal cloned from an adult cell, and kept at the Roslin Institute for animal research where she died in 2003 from lung cancer. Ian Wilmut leader of the research group derived the name from the fact that Dolly was cloned from a mammary gland cell and, sez he, “There’s no more impressive pair of mammary glands than Dolly Parton’s.”

There’s exhibitions on Ancient Egypt and East Asia, and the arguably more ancient Elton John’s suit is amongst the fashion artefacts on display. In the new building Scotland is investigated through the ages. This is rich in detail but challenging. Some years back I visited Stirling Castle, which had an excellent guided tour, along with permanent displays that clearly mapped the heritage of Scottish Kings and Queens. I didn’t really get that clear a narrative here, perhaps I was tiring. It’s a vast museum, and hard to take in everything in one day. Worth a visit, or two.

The statue guarding the entrance is of William Chambers, who asides from his love of dogs, had a notable career. Born in 1800, he opened his first bookshop at nineteen and established a publishing empire with his younger brother Robert. As Lord Provost of Edinburgh in the 1860s he initiated major street construction projects hereabouts.

Chambers Street connects to the North and South Bridges joining Old and New Towns and bisected by the Royal Mile. I’m searching for the Royal Oak, another stop on the Rebus Pub Crawl. Hidden down Infirmary Road, its modest entrance leads to a welcoming traditional bar. The pub is two centuries old and is long established as an informal folk music venue. It features in Rankin’s Set in Darkness, eleventh in the Rebus series set during the birth of Scottish devolution. A duo discusses politics at the upstairs bar while I am engaged by the young lady serving. She tells me tales of growing up on Scotland’s east coast and I can thread in vague experiences of my own including Inverness and the shores of Lough Ness. There be monsters and dragons, and bagpipe festivals, and ancient standing stones where you might catch a glimpse of Catriona Balfe flitting through timezones in a diaphanous shift. But I digress. The lady merges the two conversational groups and now we argue over the travails of Mister Trump and his chances of reelection. There’s a smoke break, and I’m left alone with the mirrors and memories, and haunting lines of musicians who have gone or yet to visit.

Last on Rankin’s list is Bennetts, another old style pub on the southern approaches. It’s on my route home to Morningside, retracing my steps back to Tollcross and onto Leven Street. Bennetts is next door to the King’s Theatre, currently closed for renovations. There’s been a pub here since 1839, its current incarnation dates to the start of the twentieth century, about the time the theatre first opened. It’s a beautiful Victorian bar with high windows, wood and brass fittings, an open fire and snug. Here I spy the bagpipe busker from outside the Academy, his weaponry laid out on the table on his LGBQT flag. The barman proposes a chocolate flavoured stout which hails, I think, from Skye. Meanwhile, beyond Bennett’s huge windows, the sky above has opened and the deluge pours upon all without. I should stay sheltered I suppose.

Further on, Bruntsfield Place rejoices in the high, neo-gothic architecture typical of the city. Bruntsfield is birthplace of Muriel Spark. Her novel the Prime of Miss Jean Brodie was published in 1961. It was filmed in 1969 starring Maggie Smith. The film depicts Jean living in this area with the school based on nearby Morningside. On one of my all too many days off school I snuck into a Dublin cinema to catch this, becoming lost in a world of Scottish schoolgirls, bohemian art and some challenging social political theory. Maggie Smith won an Oscar. I’m in m’prime!

Bruntsfield Links provides a welcome slice of greenery on the city’s edge. It is, perhaps, the founding place for the ancient game of golf. The Golf Tavern boasts of dating back to 1456. Certainly, the Links were the playground of the Edinburgh Burgess Golfing Society, now known as the Royal, which claims to be the oldest golf society in the world, formed in 1735. They became a club and moved to their own course in 1890. There is still a pitch and putt course on the Links, but most is now a public park.

From the seats outside I have a view across the links to Arthur’s Seat. Arthur’s Seat is a remnant of the ancient volcano, along with Calton Hill, and the Castle Crag. It has featured frequently in the city’s literature, with many appearances in the Rebus series. One particularly evocative scene occurs in James Hogg’s fantastical novel the Confessions of a Justified Sinner of 1824. A broken spectre on the misty mountain makes for an eerie culmination in the struggle between the two sibling protagonists, George and Robert. Robert and his evil alter ego, Gil Martin is another inspiration for Jekyll and Hyde.

The Arthur in question is said to be the legendary king of the Britons who halted the AngloSaxon advance in the sixth century. Those events and their people are lost in the mists of time. Rather as Arthur’s Seat is now. A fog, or haar, has swept over the Old Town, so that as I turn to say farewell, the spires and peaks and castle of Auld Reikie float on its murky cushion, slipping off towards the horizon. And are gone.

Time to close our evening in more mundane pursuits. Stirling is lively at night, without much by way of airs and graces, but plenty of good places to eat and drink. All you can eat at Chung’s Chinese is enough by way of temptation – the one thing I can’t resist. Return to the Hotel for a quiet beer in the bar. High windows here as in room. Schoolhouse rules apply. The ambience is pleasant and in solitude we can savour all we’ve experienced on this Scottish tour. It seems like and age, and a wee spark of time. The last day dawns damp and grey. We finish as we started on our first in Glasgow, in Wetherspoons for the best Scottish breakfast in, well, in Scotland.

Time to close our evening in more mundane pursuits. Stirling is lively at night, without much by way of airs and graces, but plenty of good places to eat and drink. All you can eat at Chung’s Chinese is enough by way of temptation – the one thing I can’t resist. Return to the Hotel for a quiet beer in the bar. High windows here as in room. Schoolhouse rules apply. The ambience is pleasant and in solitude we can savour all we’ve experienced on this Scottish tour. It seems like and age, and a wee spark of time. The last day dawns damp and grey. We finish as we started on our first in Glasgow, in Wetherspoons for the best Scottish breakfast in, well, in Scotland.