Memorial Road merges with Amiens Street as we head further north. This is transport city; seafaring ships on the river behind us, the railway curving along the Loopline to our left, while ahead Bus Aras forms a glass and steel embrace for the bus traveller.

Bus Aras is about my vintage. Blinking into the world in the mid fifties, just as I was, not far away in the Rotunda Hospital on Parnell Square. First mooted in the immediate aftermath of World War Two, it took ten years for the project to be realised. Dublin’s first modernist building, it was also emblematic of the modernist rebuilding of Europe after the war.

This significance sat uneasily with conservative Ireland. Bus Aras had to be scaled back from eight storeys to seven, providing a foretaste for Ireland’s perplexing fear of tall buildings. Ultimately, the building features two rectangular blocks of differing heights at right angles, over a circular central foyer, and a semicircular glass frontage jutting onto the concourse. It was designed by Michael Scott and a team of architects including the young Kevin Roche and Robin Walker. LeCorbusier was a major influence, enlivened by more ornate features such as the top floor pavillion and the flowing canopy sweeping along the frontage. This was the work of Ove Arup, structural engineer who would subsequently work on Sydney Opera House in the late fifties.

Through a changing scenario of clients and governments, the project proved expensive. Plans extended past functionality, with restaurants, nightclubs and cinema all planned for a multi purpose complex. High quality materials and various texturings were used: copper, bronze, terrazzo and oak Irish, and a number of expensive meals at Jammet’s thrown in; architects have to eat too.

A small newsreel cinema for waiting passengers ran for a couple of years until replaced by the Eblana theatre. Its small size and situation in the basement, next to the Ladies, led to detractors calling it the only public toilets in Dublin with their own theatre. The Eblana and its company Gemini Productions was founded by Phyllis Ryan and despite its shortcomings, and goings, survived as a theatre until 1995, premiering works by such major playwrights as Brian Friel, Tom Murphy and John B Keane.

Eblana is a name dating back to Claudius Ptolemaeus, or Ptolemy, the Greek astronomer and cartographer whose map of Ireland appeared in his Geographia in the second century AD. It appears south of the Boyne and north of the Avoca of Arklow, and is reckoned to be the first mention of Dublin in historical records. The placing looks right and the name could be a corruption of Dubh Linn, the Black Pool, used centuries later by the Vikings. There is no actual evidence of significant trading settlement hereabouts, way back when. Some scholars think Eblana may refer to areas further north which boast some evidence of Roman trade, with Loughshiny and Portrane as possibilities.

These days Busaras is central to a travel network throughout the city and country. You can even take the bus to London from here, via Holyhead. The Luas red line stops outside, connecting Connolly, next door, with Houston rail station away on the western end of the city. Eastwards, the Luas will continue past Connolly and on through the ultramodern development of the North Wall area as far as the point. There are bars, cafes and restaurants along the way, with Mayor Square providing a good oasis to stop and ponder the modern city.

Meanwhile, back on the banks of Amiens Street, Connolly Station is more than a century older than Busaras. Long known as Amiens Street Station, it was the terminus for the railway connecting Dublin and Belfast. This came into operation in 1844 as the Dublin and Drogheda Line. There was for a while a brief portage at the Boyne while the viaduct awaited construction. This provided the last link in 1853 and made the trip to Belfast a reality. The Dublin terminus was designed by William Deane Butler. It was built of Wicklow Granite and is distinguished by its ornate colonnaded facade and Italianate tower.

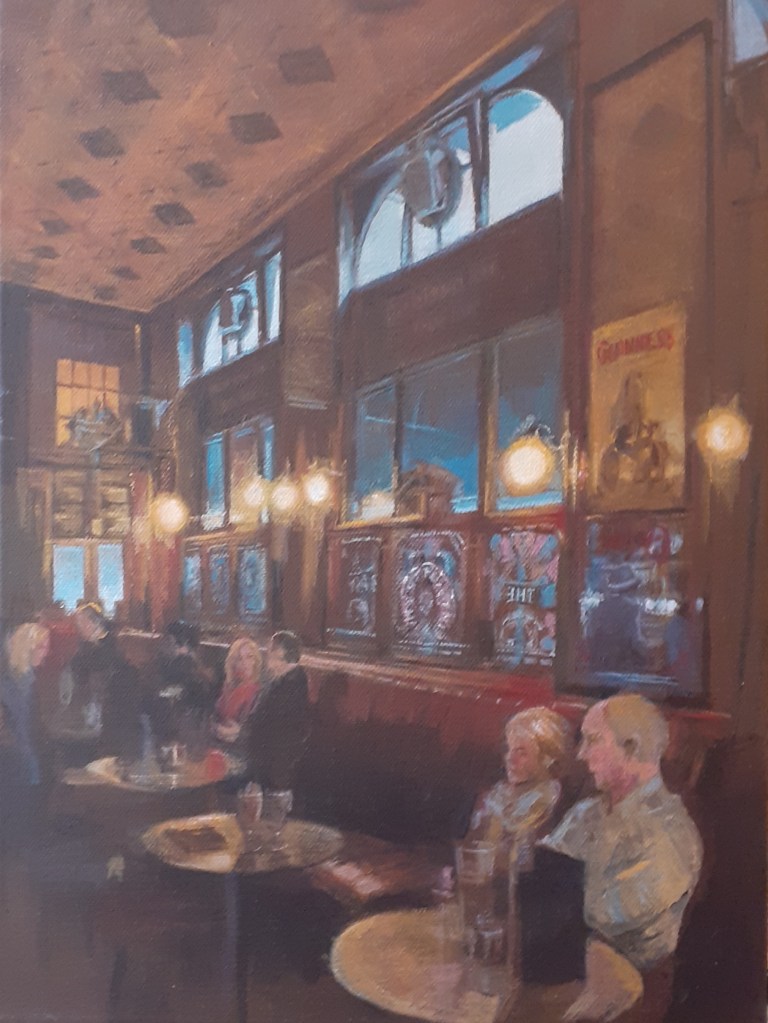

Amongst its many virtues over the years was the fact that the station bar worked as a sole oasis for the weary wayfarer. Designated a bona fide premises, that meant it could serve alcohol on days of abstinence, for the bona fide traveller. Armed only with a valid rail ticket, you could claim your reward at the bar, while luckless pedestrians waited outside in the cold and dry. The long Good Friday is no more, only Christmas Day remains as a day of abstinence; well publicly, that is. Matt Talbot would be turning in his grave. Madigans continues to serve food and drink for all who hunger and thirst, day in day out.

The Station faces down one of Dublin’s longest street vistas. The line of Talbot Street continues straight through O’Connell Street, becoming Henry Street, then Mary Street until it hits Capel Street. At 1.3km, it is almost a metric mile from the corner to Slattery’s of Capel Street. Talbot Street has nothing to do with the aforementioned Matt, it is named for Charles Cetwynd Talbot, Ireland’s Lord Lieutenant in 1820. The buildings were laid out in the 1840s at the start of the Victorian era. A certain pall of sleaze has hung in the air from early on. Monto, Dublin’s red light district in gaslight days, was just around the corner. The dreaded loopline came crashing through in 1890. Since then, such premises as the Cinerama, once the Electric Theatre, and Cleary’s pub on Amiens Street, functioned with the added sound effect of trains trundling overhead.

Talbot Street was one of three places in the capital hit by the Dublin and Monaghan bombings in1974. Fourteen of the thirty three victims died here, most of them women and including children and a full term, unborn child. The car bombs were planted by the UVF and exploded at Friday rush hour. The act was part of the Loyalist campaign against the Sunningdale Agreement which proposed a power sharing executive for Northern Ireland. Elements in British security forces, hostile to the British Labour Government, colluded. Peace would come however, twenty years later, with the Good Friday Agreement; Sunningdale for slow learners. A memorial to the victims was unveiled in 1997 and stands at the top of Talbot Street, across from Connolly.

The song Raised by Wolves from U2’s album Songs of Innocence references the event, describing the car and its registration. It features on their 2014 album, Songs of Innocence.

Boy sees his father crushed under the weight

of a cross in a passion where the passion is hate

Blue mink Ford, I’m gonna detonate and you’re dead

Blood in the house, blood on the street

The worst things in the world are justified by belief

Registration 1385-WZ