Where Killarney Road reaches its apex, a copse of fir trees guards an ancient stone marker, Saint Saran’s Cross. This mystery-laden oasis atop the hill is surrounded by a modern housing estate called Fairyhill. On the falling eastern slopes is another estate, Ripley Hills, which I call home. It was built in 1983 beside two grand houses of the nineteenth century, which were curiously conjoined: Rahan and St. Helen’s. Rahan House was once the abode of writer Arthur Conan Doyle. During his stay he developed an interest in the supernatural and wrote a book called The Coming of the Fairies.

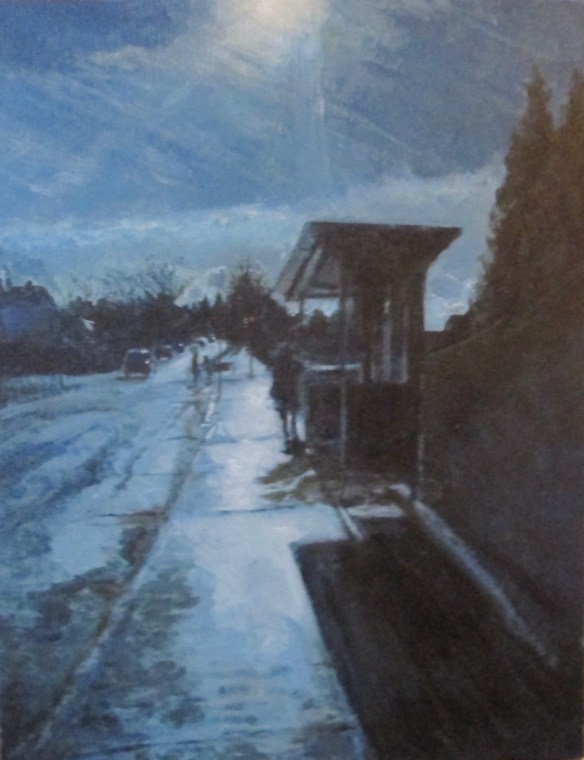

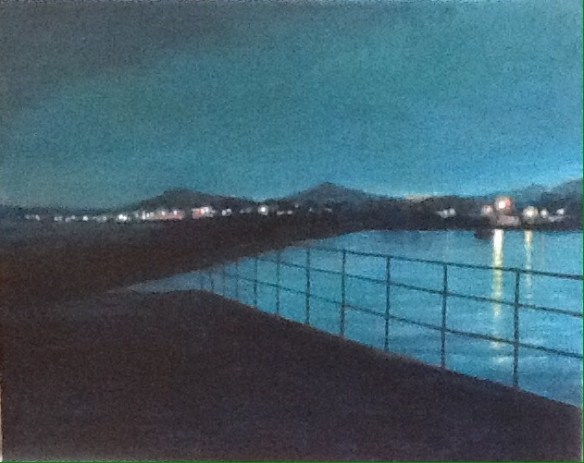

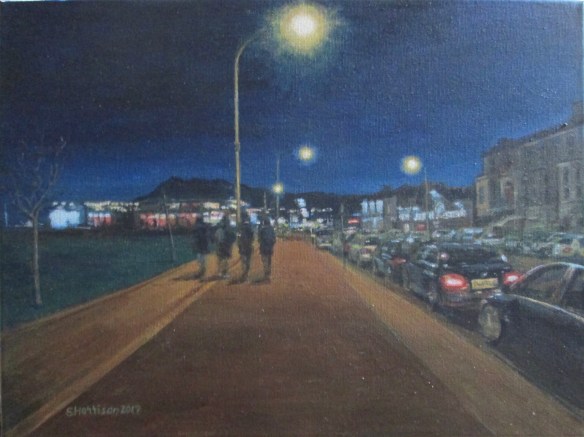

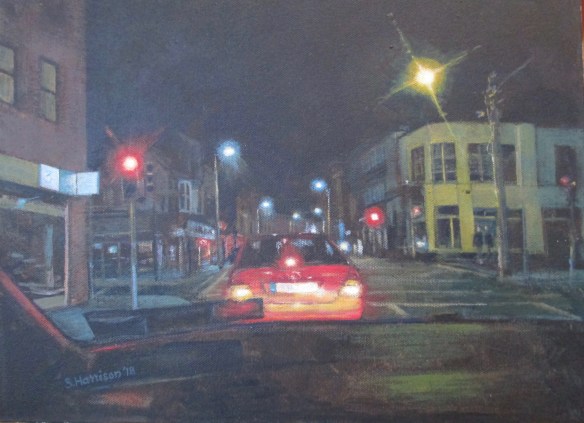

Rahan and St Helen’s were destroyed by fire shortly after I took up residence nearby and I witnessed the sad event from my rear window. They took their mysteries with them, and their only vestige is a calm green space in Ripley Court. While the urban environment continues to grow, the landscape continues to give. Fabulous views of Bray Head and the Sugarloaf Mountains are always a reward for a walk around Ripley Hills and environs. The estate itself, sylvan and landscaped is a suburban pleasure too. I have been there long enough to witness it beneath blue skies and blankets of snow. But in the dark of night, with rain falling, it is sometimes more magical still.

Something’s gotten hold of my heart

Keeping my soul and my senses apart

Something’s gotten into my life

Cutting its way through my dreams like a knife

Turning me up and turning me down

Making me smile and making me frown

You know the feeling you get when the rain is falling and falling and you stand to look up into it and feel yourself rising up until you reach that point of equilibrium where the rising spirit and the falling water are as one, poised together in endless stasis. A moment like that, held in the sodium glow of the streetlamps, is what this painting is about. Trying to capture it, I reached for a palette richer and more varied than my dark blues and greys.

Something’s gotten hold of my hand

Dragging my soul to a beautiful land

Something has invaded my mind

Painting my sleep with a colour so bright

Changing the grey and changing the blue

Scarlet for me and scarlet for you

Something’s Gotten Hold of My Heart, was written by Roger Greenaway and Roger Cook and was a hit for Gene Pitney in 1967. Born in 1940, Pitney was a singer songwriter who first achieved fame in the early sixties with movie theme songs. Perhaps his best known hit was the intense narrative Twenty Four Hours from Tulsa, a Bacharach David song in1963. His songwriting credits include Hello Mary Lou which was a hit for Ricky Nelson. In 1989 Pitney scored again with Something’s Gotten Hold of My Heart in a duet version with Mark Almond. He died in 2006.

In a world that was small

I once lived in a time there was peace with no trouble at all

But then you came my way

And a feeling unknown shook my heart, made me want you to stay

All of my nights and all of my days