Blackrock has been, since Early Modern times, the first settlement you hit south of Dublin city. It perches above the rocky shore along the rocky road to Dublin. Whack fol dol de day. From where we pass Blackrock College the town begins to emerge. The main road, which for long wound through the old village, was rerouted along the western fork at Blackrock Shopping Centre in the 1980s. This new route, Frescati Road, takes traffic towards Dun Laoghaire and the N11. Veer left and downhill for the town centre.

In olden days, the entrance to Blackrock was presided over by Frescati House. This was a grand Georgian mansion built in 1739 as Dublin’s upper classes sought property outside the teeming city. The FitzGeralds, Ireland’s largest landowners, acquired it as their summer residence from Leinster House and Carton House, Kildare. It became the home of Lord Edward Fitzgerald, a leader of the 1798 rebellion.

Lord Edward had been a veteran of the American War of Independence (fighting for the British), but later took inspiration from the French Revolution and lived in France in 1792, where he repudiated his own title and was dismissed from the army. Returning to Ireland, Fitzgerald hosted meetings of the United Irishmen at Frescati, entertaining the likes of Tom Paine, writer of the Rights of Man, and Lord Cloncurry, a neighbouring landowner. However, the movement was riddled with spies and FitzGerald was betrayed by Thomas Reynolds and forced into hiding. On the eve of the planned uprising he was captured after a gunfight on Thomas Street. FitzGerald killed an arresting officer but sustained gunshot wounds and was taken. He died from his wounds in Newgate Prison in Smithfield in 1798 at the age of thirty four.

In the late sixties, the glare of development fell upon Frescati. The unremarkable exterior may have harmed its case for preservation, still, preservationists fought a thirteen year campaign before the house was demolished to make way for Roche’s Stores shopping centre in 1983.

The town itself was first noted in the late fifteenth century and was named, prosaically, Newtown. By 1610 Newtown became Blackrock. The black rock in question is limestone calp, which appears black in the rain. With the well-to-do colonising the coast in increasing numbers. Blackrock was booming by the eighteen thirties and provided a ready customer basis for the new Dublin Kingstown railway line. The construction of the railway causeway created something of a swamp north of the town, all the way up past Booterstown. In the 1870s the town commissioners tamed the part adjacent to Blackrock and turned it into a park.

Blackrock Park provides a scenic route into town and connects to the linear coastal park by way of Williamstown Martello Tower. The Rock Road entrance takes us across a rising green lawn which culminates in a twin pillar entrance against the eastern sky. To the left of this is a monument to Irish nationalism. The commemorative garden was opened in 2016 on the centenary of the 1916 Rising. The coastal views from here are splendid. Meanwhile, to our right, entrance through the twin piers takes us into the Park proper.

The ground plunges down to an attractive pond. This forms a naturalesque amphitheatre with the sloping green sward rising above the placid water. A small circular island provides an open bandstand. Time was, my friends and I would make our way here of a weekend, where we basked in those golden days with Thin Lizzy, Mellow Candle, Horslips, and, em, Chris De Burgh. That line up played here in August 1971.

What could beat a summer’s day, full of sunshine and flower power, and a vague scented mist settled over the hollow? Mellow Candle in one of their less mellow moments would launch into the manic vocalisation: toor a loor a loor a laddy, toor a loor a lay! Leading to the refrain:

I know the Dublin pavements will be boulders on my grave

I know the Dublin pavements will be boulders on my grave!

That number finished their album Swaddling Songs, released the following year, and brought their set to a close with audience and band taking a communal plunge into the pond. The waters are still and lily padded now with visual suggestions of Pre-Raphaelite paintings, mythology and rebirth. But if I hunker down here, I swear I can detect an echo of those soundwaves rippling the leaves and water like restless ghosts.

As a designated route linking Blackrock to Booterstown, the park is open all hours. There’s a children’s playground, designated cycle path, and an outdoor gym area. Heading around the pond, there’s a folly on the larger island to the south and here the terrain is softened and shaded by mature woodland. Farther on there’s a traditional bandstand. You can exit the park uphill at an entrance taking you to Main Street, or, as I did, through a narrow lane along the railway line, emerging at the Station.

Blackrock Station is a grand two storey structure with a portico. The Railway Station opened for business in 1834, being the one stop on the original Dublin to Kingstown line, twixt Westland Row in the city and the terminus at Kingstown.

Seaward of the far platform stood the baths and swimming arena. Blackrock Baths were built by the Railway Company in 1839. Fifty years later they were enlarged, with designated bathing for men and women in separate pools. In 1928 they were used in the Tailteann Games, an Irish Olympics after Independence, with a fifty metre pool and a stand for a thousand spectators. Usage declined in the seventies, leading to closure in the eighties. Sadly, the Baths were demolished in 2013. You can still see their outline from the pedestrian bridge over the tracks to the south of the station.

There’s still bathing along the coast from a narrow strip walled off from the railway. This culminates a hundred metres or so on at an imposing structure. The new railway crossed the private beach of Maretimo House, property of Valentine Lawless, Lord Cloncurry. By way of compensation, a grandiose bridge and private harbour were constructed. Up until recently, the harbour included a small shelter, rendered mythic by its classical portico, but this has been demolished. The bridge itself with its walkway strung between two elegant towers, has been allowed to fall into disrepair and access is fenced off. Lawless, appropriately named in his younger years, had fallen in with Lord Edward and was imprisoned for sedition in the Tower of London in 1798. He fled to Europe upon his release and settled for a time in Rome. Ultimately he reconciled himself with British authority in Ireland, becoming a Viceregal advisor and a magistrate.

This is the end of the line for the coastal path, though it resumes shortly past Seapoint Dart Station. In between, we must return towards Blackrock station, overlooked by the elegant Idrone Terrace to our left, and climb up to Blackrock Main Street. Our route takes us through the village and along Newtown Avenue and Seapoint Avenue.

The main street is busy, with several coffee shops spilling onto the pavement. Blackrock Market is entered through an archway where it opens into a sizeable maze of stalls offering a cornucopia of fashion, furniture, arts and crafts, food and drink. While many such markets have been squeezed out of the marginal properties they occupy, Blackrock has clung on since its establishment in 1986.

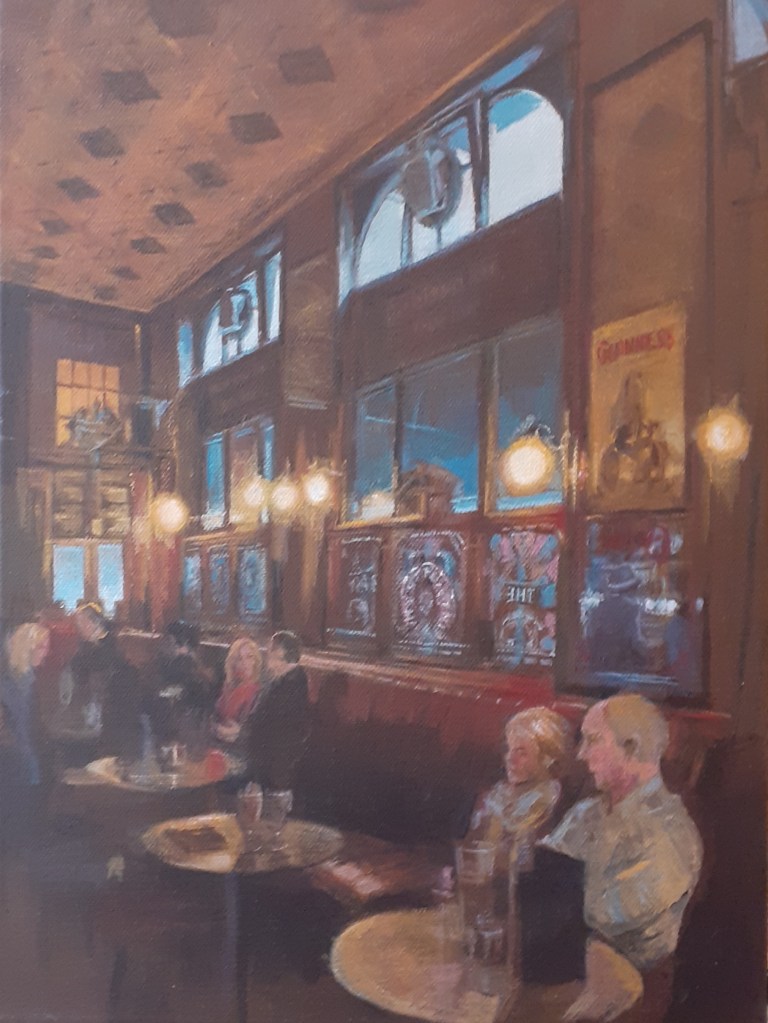

I take a pint of Guinness at Jack O’Rourke’s, the brew being a malty response to the changing of the season. And very good it is too, savoured in a slice of sunlight that chanced upon the lane to the side of the boozer. Blackrock’s bars also include the Breffni, the Wicked Wolf, Flash Harry’s and the Ten Tun Tavern. There is little concession to the drift towards al fresco in the bar trade, though you can perch on the pavement outside the Ten Tun at the southern end of Main Street.

Near the top of the town, there’s a 9th century cross. This was probably a burial marker to begin with, becoming a property marker and then from the eighteenth century the focus of a tradition marking the boundary of Dublin City. Every three years, the Mayor of Dublin and his Sheriffs would journey here formally acknowledging the cross as the southern limits of the jurisdiction of Dublin Corporation.

Main Street divides into Temple Road and Newtown Avenue. Along Temple Road, the right hand fork, we come across Blackrock Dolmen. This sculpture by Rowan Gillespie is evocative of ancient days and teeters near the entrance to the Church of Saint John the Baptist. The church was built in 1845 on land donated by Valentine Lawless and designed by Patrick Byrne, an early example of Gothic Revival, inspired by Augustus Pugin. The interior holds stained glass windows by Ireland’s two masters of the form, Harry Clarke and Evie Hone.

The left fork is Newtown Avenue, which keeps us to our coastal route. The Town Hall was completed in 1865 with the formation of the Town Commission a few years earlier. Next to the Town Hall, and forming a unified three piece, the Carnegie Library and Technical Institute were built in 1905.

Newtown Avenue leads to a sharp dogleg right, to avoid running into the front porch of Newtown House. Blackrock House from 1774 is adjacent, distinguished by its two storey brick porch. The next sharp left takes us down Seapoint Avenue. There’s a narrow laneway leading to Seapoint station. This opened in 1860 when it was called Monkstown and Seapoint. To access the coast, take the next laneway on the left which leads down to Brighton Vale, a pleasant row of bungalows nestled on the shore. A few yards further on is Seapoint Martello Tower, overlooking the popular bathing place. From here the walkway curves along the lower lip of Dublin Bay to its end.

The next station is called Monkstown and Salthill. Salthill Station dates from 1837, closed in 1960, but was reopened with the electrified Dart service in 1984. This was the site of the original terminus before it moved farther east to the current location of Dun Laoghaire station in 1837. On reaching the West Pier, we begin retracing the steps we trod on South Dublin’s Rocky Shore. So, it is possible, and very enjoyable, to walk from the Liffey estuary, all the way down to beautiful Bray, County Wicklow. From Raytown to Bray town; and beyond.