On the bend of a great river, over which is built an endless bridge, you will find the Harbour of the Moon. There I observe a middle eastern girl twirling beneath a coloured scarf, a vista across slated rooftops to a giddy spire, a couple arm in arm in an ochre laneway. Or maybe I’m not seeing things quite right. The taxi driver looks back over his shoulder and gives me the fare. He says, for you, I think, or for two. I struggle with the language. It’s been a long time.

On the bend of a great river, over which is built an endless bridge, you will find the Harbour of the Moon. There I observe a middle eastern girl twirling beneath a coloured scarf, a vista across slated rooftops to a giddy spire, a couple arm in arm in an ochre laneway. Or maybe I’m not seeing things quite right. The taxi driver looks back over his shoulder and gives me the fare. He says, for you, I think, or for two. I struggle with the language. It’s been a long time.

Bordeaux airport is reassuringly intimate. I take a small drink to the outside tables and relax. I decide on the taxi into town although this is not a great idea. It is rush hour and the journey is expensive. Fifty euro. I attampt some French with the driver who is from Le Havre. I make up stories from my interesting fictional self.

I arrive in central Bordeaux at the entrance to Capuchins Market. This lies along Cours de la Marne, a long grubby thoroughfare linking the rail station and Place de la Victoire. Walking here at night is edgy and weird. There are an unusually large amount of hairdressers which I won’t be wanting, and internet cafes which I will since my phone is kaput.

My apartment is on Rue Beaufleury, a lane that doesn’t live up to its pretty name. The apartment itself is great. I have a large terrace on the top of the building. It offers that most typically French urban view, cascading slate roofs into the distance, the horizon punctured by the mighty spire of St. Michel.

St. Aubin’s Pub is one of many on the wide cobbled expanse of Victoire. The waiters wear black kilts, creating its own culture bubble; a sort of Caledonian Gallic. I enjoy a drink here at night. To one side, motor traffic streams relentlessly into the plaza. All around nightbirds display their plumage. The university is scattered nearby and this is a major student venue, so it’s lively and pleasant.

Rue St Catherine links the plaza and the city centre. The longest street in the city maintains the straight line of the original Roman Road. The Emperor Augustus established Bordeaux as the centre of the new province of Aquitania in 16AD. Some vestiges of Rome remain, the idea of empire persisting in the flourishes of later regimes.

Bordeaux’s medieval walls are traceable if not extant. Some portals remain. The Grosse Cloche straddling Rue St. James, just off Cours Victor Hugo, is an extravagant gothic tower dating from the fifteenth century. Such structures provoke the imagination into visions of love and death, the spinning coin of chivalry.

St Catherine, ancient in origin, is well suited as the artery of commerce, thronged with the constant footfall of shoppers. The back streets weave more intricate and seductive patterns, hiding a medieval heart. Bordeaux boomed in the eighteenth century, the Age of Enlightenment, becoming a preferred port of trade with the West Indies, importing cotton, sugarcane and those elixirs of life; coffee and tobacco. Prosperity reformed the city in the modern, rationalist manner. Fine mansions lined grand boulevards to create a unified triumph of Neoclassical architecture. Most of it remains and Bordeaux has been spared the depredations of unsympathetic development.

St Catherine is entered through a triumphal-style arch. Porte d’Aquitaine was built in 1750 and was a functioning modern city gate with a toll lodge attached. The grand arch remains in isolation, fulfilling its function of landmark. Within this parameter, the city is largely pedestrianised. Crowded too. Rarely did I find myself alone at cafe or bistro. On the street there is a constant charge.

This bright sunny morning, I step off life’s merry-go-round onto Cours Alsace Lorraine leading to the relaxed Civic and Museum quarter. The Cathedral St. Andre dominates an expansive yet intimate square framed also by the Hotel de Ville. Outside a Bistro I sip a cool one, watch congregations ebb and flow in the sunshine. The Hotel de Ville is open and welcoming, with an ever changing rota of wedding groups. Built on the cusp of revolution in 1784, it set the tone for the wave of elegant Neoclassicism that swept Bordeaux.

The Cathedral meanwhile, is sharply imposing. Twin steeples soar above the square. Circling clockwise, the heavily buttressed west wall dates back to the church’s foundation in the eleventh century. It has been madeover many times since. Most striking feature of this ancient stone tableau, the free-standing 15th century Tour Pey-Berland is topped by a golden statue of Our Lady of Aquitaine. Within, ornate vaulted ceilings sweep up to literal and metaphorical heaven. One end wall is occupied by the magnificent organ. It is surprisingly bright, slanted sunlight a solid presence in the interior space. There is a small exhibition of selected icons in an ante room, including another suggestion of Scotland in St Andre’s crucifixion on a saltire, and the Crucifixion of Christ by Rembrandt.

The Musee des Beaux Artes is hidden behind the Hotel de Ville in twin buildings each side of a quiet green. It hosts a quirky, piecemeal slant on Bordeaux’s place in French Art. Breughel, Rubens and Titian feature amongst the earlier European painters. Romanticism is to the fore: ships savaged by boiling seas, seductive nudes on storm tossed sheets, and of course Delacroix. Calmer, if no less passionate, Impressionist souls include Renoir and Morisot. I exit through the surreal screened walkway linking the buildings; a trompe l’oeil collage of art through time.

Bordeaux is a river port. The Garonne snakes northwest heading for the Bay of Biscay. Parks and esplanades have been laid out here, but nowhere to put in for refreshment nor much, beyond the vista, by way of visitor attraction. The Pont de Pierre, built by Napoleon Bonaparte to facilitate his Spanish campaigns, became the first city bridge to span the Garonne. Few followed, the river simply too wide for the far bank to be included in the definition of Bordeaux. There’s something strange about walking a bridge, which in its detail is a typical nineteenth century succession of arches, seventeen in all, but in its scale seems endless. It suggests a bridge to the afterlife, the almost banal familiarity subverted by the eerie suggestion of infinity.

Bordeaux is a river port. The Garonne snakes northwest heading for the Bay of Biscay. Parks and esplanades have been laid out here, but nowhere to put in for refreshment nor much, beyond the vista, by way of visitor attraction. The Pont de Pierre, built by Napoleon Bonaparte to facilitate his Spanish campaigns, became the first city bridge to span the Garonne. Few followed, the river simply too wide for the far bank to be included in the definition of Bordeaux. There’s something strange about walking a bridge, which in its detail is a typical nineteenth century succession of arches, seventeen in all, but in its scale seems endless. It suggests a bridge to the afterlife, the almost banal familiarity subverted by the eerie suggestion of infinity.

I remain on the South Bank. An eighteenth century ornamental arch, Porte de Bourgogne, marks the entrance to the city. The bridge terminal connects to Cours Victor Hugo, a wide, curving crosstown thoroughfare that fair crackles with all the quirks and cultures of city life. I experience that redolent sense of nostalgia. Something about the bustle, the flea market ambience, the hodge podge of immigrant shops and exotic food outlets. There’s maybe a whiff of patchouli, or something stronger, so’s I’m back in the day, a young adult at large, hair blowing wild, eyes like headlamps seeing wonder in the everyday.

I return to the buildings on the riverfront. This is an Arab quarter, and the cafes are packed with men sinking strong coffee, smoking and talking. The tower of St Michel guides me on. One of the tallest in France, it is a masterpiece of fabulous Gothic, standing free of the church, as is common here. The fifteenth century original was destroyed in a lightning storm in 1760. Reconstruction only began a century later.

This Sunday morning, with the street market in full swing all around Place Canteloupe, it is even more separate, a focal point around which stalls and entertainers set up, while groups lounge and laugh on its steps and under its arches. There is a bewildering swirl of scents and sounds, a throbbing sensuality rising with the tower to the blue heavens. The sidewalk restaurants are crammed and I note with mouth watering intent the generous and varied Moroccan dishes: tempting tagines, rack of lamb, soft beds of couscous, steaming stew, chick peas and spicy sauces.

Within the church it is surprisingly calm despite a good crowd of devotees. The churches here do not have pews but individual seats. Unfortunately, some resident idiot has decided to move them all loudly a foot to the right as I sit in attempted prayer. Time to weather the human storm again so.

Within the church it is surprisingly calm despite a good crowd of devotees. The churches here do not have pews but individual seats. Unfortunately, some resident idiot has decided to move them all loudly a foot to the right as I sit in attempted prayer. Time to weather the human storm again so.

Outside the plaza still swirls like a calliope. A young woman dances and spins beneath coloured scarves to a woman playing a bodhranesque drum. There is an African or Middle Eastern beat, insistent with familiarity. I know this song. It has a place on my car stereo. Deva Pravel chanting the Moola Mantra:

Om

Sat Chit Ananda Paraprahma

Purushothama Paramatma

Shri Bhagavathu Sametha

Shri Bhagavatha Namaha

Hare Om tat sat Hare Om tat sat

Hare Om tat sat

Hare Om tat sat

I determine on a couscous having been assailed by that African aroma throughout San Michel. Restaurant Le Marrakech on Rue St Remi is quiet; lush red velvet drapes and subdued lighting striking just the right tone. The couscous is superb, generous and varied in every sense. The friendly waiter, who is from Pakistan, stands me a sizable digestif. Down the hatch!

Heading home by St Catherine, i spot The Blarney Stone Bar crossing Victor Hugo. It is good to sink an Irish Pint at the end of the night. I had been drinking earlier with the other side. The English flagged Houses of Parliament serves Carlsberg Elephant. The Blarney’s barman tells me that’s seven per cent. No wonder I was elephants. I compliment the barman on his creamy head. And the pint was good too.

Heading home by St Catherine, i spot The Blarney Stone Bar crossing Victor Hugo. It is good to sink an Irish Pint at the end of the night. I had been drinking earlier with the other side. The English flagged Houses of Parliament serves Carlsberg Elephant. The Blarney’s barman tells me that’s seven per cent. No wonder I was elephants. I compliment the barman on his creamy head. And the pint was good too.

Night falls, streetlights bloom and Rue Beaufleury waxes to its name. In the blue doorway of the ochre lane, a woman lounges. She holds her cigarette upright and blows it aflame. There is a heavy scent in the air, like patchouli oil. She gestures by that slight inclination of head. If you want, she says, there is a place the far side of Capucins. The market is ferme. But beyond you will see young men drinking and beside the bar there is a doorway. There you can get some. If you want.

Night falls, streetlights bloom and Rue Beaufleury waxes to its name. In the blue doorway of the ochre lane, a woman lounges. She holds her cigarette upright and blows it aflame. There is a heavy scent in the air, like patchouli oil. She gestures by that slight inclination of head. If you want, she says, there is a place the far side of Capucins. The market is ferme. But beyond you will see young men drinking and beside the bar there is a doorway. There you can get some. If you want.

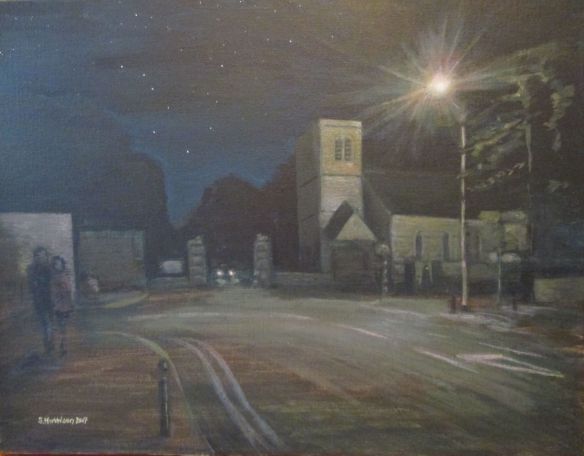

There is no movement in the street. The graffiti says in English: Death to Graffiti Artists. A taxi drifts past. A face I recognise swivels towards me on passing. I nod. The tail lights take red serpents along the lane. A chimera persists on the alley’s horizon: an indeterminate couple arm in arm beneath a perfect lunar sickle. In the Harbour of the Moon, the old nestles in the new moon’s arms.

Alhambra signifies the Red Castle, from the blood toned colour of its stone. The Moors had built a fortress here in the ninth century but the existing complex dates to 1333 when Yusuf I, Sultan of Granada, established his royal palace. It was to be the last bastion of the Moor in Spain, In 1492 the Catholic Monarchs, Ferdinand and Isabella, completed the Reconquista when they defeated the Emirate of Granada. The two monarchs entered Granada clad symbolically as Moslems, promising friendship and tolerance of religion. It was short lived. The Moors rebelled in 1500 and the treaty lapsed. Moslem and Jew were required to convert or leave. The institution of the Spanish Inquisition was set up to police this law.

Alhambra signifies the Red Castle, from the blood toned colour of its stone. The Moors had built a fortress here in the ninth century but the existing complex dates to 1333 when Yusuf I, Sultan of Granada, established his royal palace. It was to be the last bastion of the Moor in Spain, In 1492 the Catholic Monarchs, Ferdinand and Isabella, completed the Reconquista when they defeated the Emirate of Granada. The two monarchs entered Granada clad symbolically as Moslems, promising friendship and tolerance of religion. It was short lived. The Moors rebelled in 1500 and the treaty lapsed. Moslem and Jew were required to convert or leave. The institution of the Spanish Inquisition was set up to police this law.

This area overlooking the Darro is the Albaicin, dating back to the 13th century and rich in Moorish heritage. The streets meander past high walled villas, dazzling white washed walls and towering palms and pines. Becoming impossibly narrow so you feel you must turn back, then widening unexpectedly into sparsely imposing squares. Quiet and weird; at times I feel I’ve strayed into a Dali scenario; Outskirts of the Paranoiac, perhaps.

This area overlooking the Darro is the Albaicin, dating back to the 13th century and rich in Moorish heritage. The streets meander past high walled villas, dazzling white washed walls and towering palms and pines. Becoming impossibly narrow so you feel you must turn back, then widening unexpectedly into sparsely imposing squares. Quiet and weird; at times I feel I’ve strayed into a Dali scenario; Outskirts of the Paranoiac, perhaps.

Heading west from Phibsborough, we keep left at St. Peter’s Church. This was built piecemeal from the 1830s as Catholicism asserted itself in post Emancipation Dublin. The present grand gothic structure incorporates the original Catholic school, betrayed by its more fortress like design. The imposing tower, rising two hundred feet, brought the project to fruition in 1910. The splendour of the interior is enhanced by the stained glass windows, including a Harry Clarke from 1919. From here, the North Circular takes on a more salubrious appearance. The street is tree lined and this lazy Sunday afternoon the dappled light grants the illusion of passing through a painting. It is an elegant, if shabby genteel, avenue from here to the Phoenix Park.

Heading west from Phibsborough, we keep left at St. Peter’s Church. This was built piecemeal from the 1830s as Catholicism asserted itself in post Emancipation Dublin. The present grand gothic structure incorporates the original Catholic school, betrayed by its more fortress like design. The imposing tower, rising two hundred feet, brought the project to fruition in 1910. The splendour of the interior is enhanced by the stained glass windows, including a Harry Clarke from 1919. From here, the North Circular takes on a more salubrious appearance. The street is tree lined and this lazy Sunday afternoon the dappled light grants the illusion of passing through a painting. It is an elegant, if shabby genteel, avenue from here to the Phoenix Park.  To the south is the extensive area of Grangegorman. This was a manor estate during the middle ages with extensive orchards. Dublin city has crept around it but oddly not through it. Grangegorman remains as a large undeveloped slice of the crowded capital. The population of Dublin’s dowdy westside was largely poor and so the area was seen as suitable for siting a variety of the more sombre Victorian institutions. A House of Industry, basically a poorhouse, was established here and around this sprouted the Richmond Lunatic Asylum, the Richmond Hospital and a penitentiary. The area persisted under this cautionary cloud until recently. St Brendan’s Psychiatric Hospital, the largest such facility in Ireland closed its doors in 2013 after nearly two centuries. Major development is underway, incorporating a campus for DIT (Dublin Institute of Technology, or Didn’t get Into Trinity as the joke goes).

To the south is the extensive area of Grangegorman. This was a manor estate during the middle ages with extensive orchards. Dublin city has crept around it but oddly not through it. Grangegorman remains as a large undeveloped slice of the crowded capital. The population of Dublin’s dowdy westside was largely poor and so the area was seen as suitable for siting a variety of the more sombre Victorian institutions. A House of Industry, basically a poorhouse, was established here and around this sprouted the Richmond Lunatic Asylum, the Richmond Hospital and a penitentiary. The area persisted under this cautionary cloud until recently. St Brendan’s Psychiatric Hospital, the largest such facility in Ireland closed its doors in 2013 after nearly two centuries. Major development is underway, incorporating a campus for DIT (Dublin Institute of Technology, or Didn’t get Into Trinity as the joke goes).  Oxmantown and Stoneybatter were other ancient settlements beyond the city walls. How ancient you can tell by the fact that Oxmantown rejoices in a weirdly Viking nomenclature.

Oxmantown and Stoneybatter were other ancient settlements beyond the city walls. How ancient you can tell by the fact that Oxmantown rejoices in a weirdly Viking nomenclature. A detour at Prussia Street, along Manor Street takes us to Stoneybatter. This is a bilingual stew of the original Irish: Bothar na gcloigh. This means Road of Stones, mangled over time to become Stoney-Batter. The irish word for road, bothar, also tells a tale. It literally means cow-path

A detour at Prussia Street, along Manor Street takes us to Stoneybatter. This is a bilingual stew of the original Irish: Bothar na gcloigh. This means Road of Stones, mangled over time to become Stoney-Batter. The irish word for road, bothar, also tells a tale. It literally means cow-path  Leaving the Glimmer Man, we return to our circular path. The final section is sylvan and suburban as far as the Phoenix Park. The avenue, lined by elegant if well worn Victorian houses, stops at the park gates, but the vista culminates further on at the Wellington memorial. The giant obelisk, rising to over two hundred feet, is a notable landmark of the city. It was built in homage to the Duke of Wellington, Arthur Wellesley, after his success against Napoleon at Waterloo. Wellington is alleged to have disparaged his birthplace by saying that being born in a stable doesn’t make one a horse. The phrase derives from Daniel O’Connell by way of lampooning the Duke’s pretensions. I imagine the thought must have crossed Wellesley’s mind once or twice, all the same.

Leaving the Glimmer Man, we return to our circular path. The final section is sylvan and suburban as far as the Phoenix Park. The avenue, lined by elegant if well worn Victorian houses, stops at the park gates, but the vista culminates further on at the Wellington memorial. The giant obelisk, rising to over two hundred feet, is a notable landmark of the city. It was built in homage to the Duke of Wellington, Arthur Wellesley, after his success against Napoleon at Waterloo. Wellington is alleged to have disparaged his birthplace by saying that being born in a stable doesn’t make one a horse. The phrase derives from Daniel O’Connell by way of lampooning the Duke’s pretensions. I imagine the thought must have crossed Wellesley’s mind once or twice, all the same.  Bringing the northern semi-circle of our odyssey to a close offers a few alternatives. Technically, the route descends via Infirmary Road to Parkgate Street, where a sharp right onto Conyngham Road takes us along the walls of the Park, above the Liffey valley to Islandbridge. Alternatively, a meander through this quadrant of the Park is very pleasant. The Phoeno is worth a section to itself, so I’ll leave that for another day. I’ll finish with Philo:

Bringing the northern semi-circle of our odyssey to a close offers a few alternatives. Technically, the route descends via Infirmary Road to Parkgate Street, where a sharp right onto Conyngham Road takes us along the walls of the Park, above the Liffey valley to Islandbridge. Alternatively, a meander through this quadrant of the Park is very pleasant. The Phoeno is worth a section to itself, so I’ll leave that for another day. I’ll finish with Philo:  On the bend of a great river, over which is built an endless bridge, you will find the Harbour of the Moon. There I observe a middle eastern girl twirling beneath a coloured scarf, a vista across slated rooftops to a giddy spire, a couple arm in arm in an ochre laneway. Or maybe I’m not seeing things quite right. The taxi driver looks back over his shoulder and gives me the fare. He says, for you, I think, or for two. I struggle with the language. It’s been a long time.

On the bend of a great river, over which is built an endless bridge, you will find the Harbour of the Moon. There I observe a middle eastern girl twirling beneath a coloured scarf, a vista across slated rooftops to a giddy spire, a couple arm in arm in an ochre laneway. Or maybe I’m not seeing things quite right. The taxi driver looks back over his shoulder and gives me the fare. He says, for you, I think, or for two. I struggle with the language. It’s been a long time.

Bordeaux is a river port. The Garonne snakes

Bordeaux is a river port. The Garonne snakes

Within the church it is surprisingly calm despite a good crowd of devotees. The churches here do not have pews but individual seats. Unfortunately, some resident idiot has decided to move them all loudly a foot to the right as I sit in attempted prayer. Time to weather the human storm again so.

Within the church it is surprisingly calm despite a good crowd of devotees. The churches here do not have pews but individual seats. Unfortunately, some resident idiot has decided to move them all loudly a foot to the right as I sit in attempted prayer. Time to weather the human storm again so.

Heading home by St Catherine, i spot The Blarney Stone Bar crossing Victor Hugo. It is good to sink an Irish Pint at the end of the night. I had been drinking earlier with the other side. The English flagged Houses of Parliament serves Carlsberg Elephant. The Blarney’s barman tells me that’s seven per cent. No wonder I was elephants. I compliment the barman on his creamy head. And the pint was good too.

Heading home by St Catherine, i spot The Blarney Stone Bar crossing Victor Hugo. It is good to sink an Irish Pint at the end of the night. I had been drinking earlier with the other side. The English flagged Houses of Parliament serves Carlsberg Elephant. The Blarney’s barman tells me that’s seven per cent. No wonder I was elephants. I compliment the barman on his creamy head. And the pint was good too.  Night falls, streetlights bloom and Rue Beaufleury waxes to its name. In the blue doorway of the ochre lane, a woman lounges. She holds her cigarette upright and blows it aflame. There is a heavy scent in the air, like patchouli oil. She gestures by that slight inclination of head. If you want, she says, there is a place the far side of Capucins. The market is ferme. But beyond you will see young men drinking and beside the bar there is a doorway. There you can get some. If you want.

Night falls, streetlights bloom and Rue Beaufleury waxes to its name. In the blue doorway of the ochre lane, a woman lounges. She holds her cigarette upright and blows it aflame. There is a heavy scent in the air, like patchouli oil. She gestures by that slight inclination of head. If you want, she says, there is a place the far side of Capucins. The market is ferme. But beyond you will see young men drinking and beside the bar there is a doorway. There you can get some. If you want.

Heading north on Guild Street, the Royal Canal to our right seeps towards the Liffey. A new city, linear and rational is being stamped over the old North Wall docklands. That’s the feeling crossing Mayor Street where the Luas Red Line takes passengers arrow straight from Connolly Station to the Point Village. The Point Depot at the eastern end of the Docks is the major venue for indoor concerts. I saw Bob Dylan there some years back. A man with a hat playing piano. I could have spent the evening out in the real world, where the Liffey melts into the sea. I could have sat contentedly and watched the river flow, the memory of Bob’s music stronger in my blood.

Heading north on Guild Street, the Royal Canal to our right seeps towards the Liffey. A new city, linear and rational is being stamped over the old North Wall docklands. That’s the feeling crossing Mayor Street where the Luas Red Line takes passengers arrow straight from Connolly Station to the Point Village. The Point Depot at the eastern end of the Docks is the major venue for indoor concerts. I saw Bob Dylan there some years back. A man with a hat playing piano. I could have spent the evening out in the real world, where the Liffey melts into the sea. I could have sat contentedly and watched the river flow, the memory of Bob’s music stronger in my blood.  At Ferryman’s Crossing, a rusty reminder of the old days rises in the form of a decrepit crane. The old docklands peep through, first the palimpsest, then the ancient script itself. It’s still being written. Often the same old story. Sheriff Street runs parallel to the quays but remains remote from the modern narrative there. The area has a rough inner city reputation.

At Ferryman’s Crossing, a rusty reminder of the old days rises in the form of a decrepit crane. The old docklands peep through, first the palimpsest, then the ancient script itself. It’s still being written. Often the same old story. Sheriff Street runs parallel to the quays but remains remote from the modern narrative there. The area has a rough inner city reputation.  The Church of St. Laurence O’Toole marks the start of Seville Place. It was built in the Famine years and opened in 1850. Along Seville Place, the grandly named First to Fourth Avenues suggest New York. In fact, these are short, cottage lined cul de sacs. Under the railway bridge we reach Amiens Street.

The Church of St. Laurence O’Toole marks the start of Seville Place. It was built in the Famine years and opened in 1850. Along Seville Place, the grandly named First to Fourth Avenues suggest New York. In fact, these are short, cottage lined cul de sacs. Under the railway bridge we reach Amiens Street. This street provides Dublin’s main transport and communications hubs. Connolly Station, topped by an ornate Italianate tower was opened in 1944 as Dublin station, later named Amiens Street. By 1853 it served the rail link to Belfast. Madigan’s Pub, on the main concourse, was a Mecca for thirsty travelers on long, dry, Good Friday. It is the most central of all bonafide pubs. You would need a train ticket to deserve a pint, of course; a small price to pay. Such quaint customs are now consigned to the slop tray of history, as Ireland’s Good Friday prohibition has been lifted.

This street provides Dublin’s main transport and communications hubs. Connolly Station, topped by an ornate Italianate tower was opened in 1944 as Dublin station, later named Amiens Street. By 1853 it served the rail link to Belfast. Madigan’s Pub, on the main concourse, was a Mecca for thirsty travelers on long, dry, Good Friday. It is the most central of all bonafide pubs. You would need a train ticket to deserve a pint, of course; a small price to pay. Such quaint customs are now consigned to the slop tray of history, as Ireland’s Good Friday prohibition has been lifted.  A little further off track, Bus Aras, nearer the river, was an early modernist pile. Designed by Michael Scott and completed in 1955, from here you can take a bus to anywhere in Ireland, or all the way to London. Bus Aras and Connolly combine to form a startling urban portal, full of the contrasts of history and architecture. At just the right spot, the panorama includes Victorian Connolly Station, Georgian Custom House, the International Financial Services Centre and the Ulster Bank HQ across the river.

A little further off track, Bus Aras, nearer the river, was an early modernist pile. Designed by Michael Scott and completed in 1955, from here you can take a bus to anywhere in Ireland, or all the way to London. Bus Aras and Connolly combine to form a startling urban portal, full of the contrasts of history and architecture. At just the right spot, the panorama includes Victorian Connolly Station, Georgian Custom House, the International Financial Services Centre and the Ulster Bank HQ across the river. At more civilised hours we could repair to Cleary’s pub, beneath the bridge, shuddering under the weight of passing trains. Old style boozer of dark wood, sparse light on glinting glasses being raised at the long bar. One more toast before boarding the Gravy Train. Last wet my whistle here with Davin, on our way with to the Red Hot Chilli Peppers at Croke Park farther north.

At more civilised hours we could repair to Cleary’s pub, beneath the bridge, shuddering under the weight of passing trains. Old style boozer of dark wood, sparse light on glinting glasses being raised at the long bar. One more toast before boarding the Gravy Train. Last wet my whistle here with Davin, on our way with to the Red Hot Chilli Peppers at Croke Park farther north. At the junction of Seville Place and Amiens Street, we’re back on track. Heading North by Northwest is Portland Row, leading to the North Circular proper. Amidst the grimy urban bustle sits the landmark of the Five Lamps, delicate and redolent of a bygone age. It sits on a junction of five streets. Again weirdly suggestive of Old New York’s Five Points, notorious focus for Irish gangs in the mid nineteenth century. The eponymous, though fictional, Dublin gang appear in Bob Geldof’s Rat Trap:

At the junction of Seville Place and Amiens Street, we’re back on track. Heading North by Northwest is Portland Row, leading to the North Circular proper. Amidst the grimy urban bustle sits the landmark of the Five Lamps, delicate and redolent of a bygone age. It sits on a junction of five streets. Again weirdly suggestive of Old New York’s Five Points, notorious focus for Irish gangs in the mid nineteenth century. The eponymous, though fictional, Dublin gang appear in Bob Geldof’s Rat Trap: