Drogheda guards the mouth of the Boyne, just thirty miles north of Dublin city centre. With a population of forty thousand it is Ireland’s largest town, the sixth largest urban centre after the major cities. It is one of Ireland’s most ancient towns. Although myth persists that it developed in Celtic times, there is no solid evidence of this. Nor, unlike other large settlements like Dublin and Waterford, were the Danes prominent. It fell to their cousins the Normans to establish the place.

In Ireland’s ancient east, the Boyne valley has long been a crucial axis. Newgrange is situated just five miles to the west, indicating that the area was well settled by neolithic times, c. 3000BC. The hinterland of County Meath terminates at this coastal appendage. Meath in Gaelic denotes the middle, and this was the centre of Celtic power radiating from Tara. This centrality formed a constant thread in much of the tapestry of Irish history.

We drive in early of a morning from Dublin airport, under a polished abalone sky. We’re taking the coastal route, via the growing conurbation of Laytown – Bettystown – Mornington. This is coastal County Meath, an area with a whiff of the ancient art of seaside holidays. The behemoth of the Butlin’s holiday camp at Mosney is nearby. Once the focal point for Irish families relentless pursuit of fun, it is now a centre for asylum seekers.

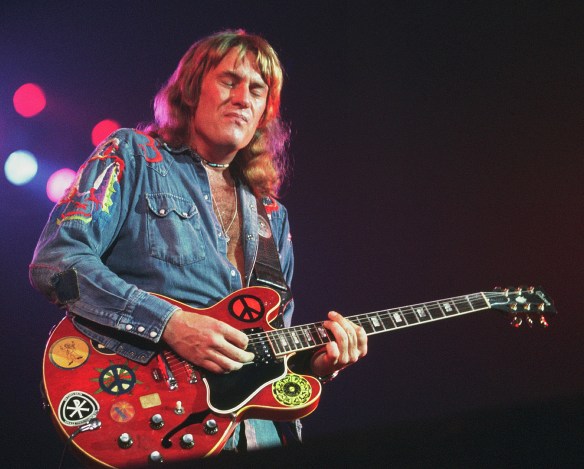

I am just a poor boy though my story’s seldom told

I have squandered my resistance for a pocketful of mumbles

such are promises

A sharp turn at the mouth of the River Boyne takes us barrelling towards Drogheda. The railway viaduct dominates the scene. Designed by Irish engineer, Sir John Benjamin McNeill, using radical new techniques in its construction in1853, on its completion it was regarded as something of an engineering wonder. It is a hundred feet high with twelve soaring stone arches on the southern bank, and three on the northern, linked by three iron truss spans. Prior to completion, passengers on the Dublin Belfast line were required to hike through Drogheda to make their connection.

In the shadow of the southern arches, we pause at Ship Street, a quaint terrace of nineteenth century industrial houses at right angles to the river. All quiet at this hour, but just as obviously occupied. There’s a homely scattering of toys and street furniture, paraphernalia waiting for another day. A rich atmosphere of story and history pervades, emitting its own rugged urban charm.

We find a convenient parking space on South Quay. The old town and County Louth lie across the river. Along the once green, grassy slopes of the Boyne, the modern town pushes through. The fording point is dominated by an ancient defense. The motte and bailey castle, Millmount Fort, was built by Hugh De Lacy, the Norman Lord of Meath in 1189 atop a large mound on the southern bank. It has featured in Cromwell’s siege of 1649 and during the Irish Civil War of the 1922. Cromwell’s sacking of the town is one of the most traumatic events in Irish history. Cromwell decimated the garrison but also massacred hundreds of citizens, especially Catholics, in what remains a serious stain on his reputation. Today, Millmount is crowned with a Martello Tower, a link in the coastal defence chain from the Napoleonic Wars. Its appearance means locals oft refer to it as the Cup and Saucer,

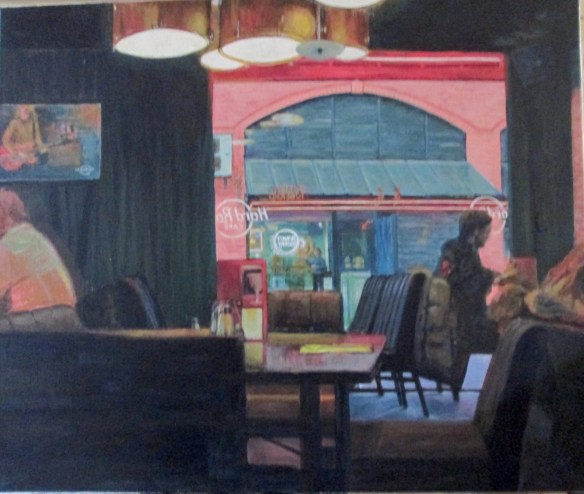

It’s early morning as we wend our way uptown from South Quay. There’s a beguiling mix of smalltown and bigtown, as morning deliverymen trade banter. We are included without demur. I see you’re a visitor, says one. Camera gave it away, did it? People here don’t seem shy of interaction. Topping the rise of Shop Street, another cup and saucer suggests itself with the aromatic beckoning of coffee, courtesy of Cafe Ariosa. We sit at slanted pavement tables on St Laurence Street and charge our batteries on weak sun and strong caffeine.

St Peter’s RC church is the towering feature on West Street, which could be described as the town’s Main Street. Designed by J O’Neill and WH Byrne in the French Gothic Revival Style in 1884, it spears the heavens with its dazzling spire. An earlier church of 1793, designed by Francis Johnson, architect of Dublin’s GPO, is incorporated into the new church. St. Peter’s is a renowned repository of relics. It boasts a relic of the True Cross, gifted by Ghent Cathedral on account of their shared connection with Saint Oliver Plunkett. St Peter’s is famously where one can view the head of the Saint.

Plunkett was the bishop of Armagh and Primate of Ireland, beatified in 1920 and canonised in 1975, the first Irish saint for seven centuries. He was born in 1625 in Loughcrew, that most ancient of spiritual sites in Meath. In 1681 Plunkett was implicated in intrigue following the Popish Plot of Titus Oats. Attempts to try him for treason in Ireland collapsed and the authorities removed him to England to expedite conviction. Although King Charles II knew him to be innocent, he dared not intervene, out of concern for his own head, one supposes. The accusers had their way, and Plunkett became the last Catholic martyr in England, on his execution at Tyburn in 1681. His remains were exumed and moved to Germany, with the head first taken to Rome , on to Armagh and then to Drogheda in 1921, where it is housed in an ornate shrine at St Peter’s.

By implication, West Street is mirrored by East Street across town. Now called St Laurence Street, it culminates in the former East Gate, now St. Laurence Gate. This is a barbican gate from the thirteenth century. Two huge four storey towers are joined by a viewing bridge, giving excellent views of the Boyne estuary. and at street level by a crenellated archway.

St. Laurence’s Gate features on the coat of arms with three lions and a ship emerging from each side, illustrating the significance of mercantile trade in the town’s fortunes.The association with England, three lions and all, is also notable. None of which elements saved the town from the wrath of Cromwell. But, it survived and prospered once more.

Returning down Constitution Hill, we cross the elegantly modern Hugh De Lacey pedestrian bridge to our car at South Quay. At this crux of the modern town, it is interesting that the featured monument is a lifesize figure of Tony Socks Byrne, who won a boxing bronze at the Melbourne Olympics in 1956. Rendered by French born sculptor Laury Dizengremel, there is something in its quiet realism that embodies the human spirit.

Outside Ariosa Cafe, teetering on the sidewalk as the growing stain of autumn morning sun seeps into the monochrome. At the adjacent table an amiable gent engages passersby in verbal exchange, familiar and casual. He is, I presume, a notary of sorts, and this high street village rapport has an appropriate touch of the medieval about it. You close your eyes, and open them again. And nothing much changes through the ages. People, in whatever manifestation, in times of plenty or times of interest, are resilient. They are the essence of any place.

In the clearing stands a boxer and a fighter by his trade

and he carries the reminders of every glove that laid him down

or cut him till he cried out in his anger and his shame

I am leaving, I am leaving, but the fighter still remains

(The Boxer/ Paul Simon)