Swingboats are a metaphor for love. You are both in the same boat, swinging together, held close and apart by centrifugal force, sawing between ecstasy and nausea, seeing nothing but your love and a swirling sky. Shortly after moving to Bray, M decided to test this particular equation with a full on swingboat ride. When my head stopped spinning, a half hour or so after touchdown, I realised I had enjoyed it. This proved useful in rearing our children. Children, I soon discovered, like nothing better than being propelled through space at dizzying speeds with clashing trajectories. Helter skelter, ferris wheel, and dodgems, and several infernal modern devices, are magnetic attractions. There is no opting out. The only way to keep nausea at bay is to scream or, and certainly if you’re a man, shout.

Where better to try it out. Bray was granted its license for market and annual fair by King John in 1213. At the southern extreme of the Pale, it was defended by a couple of castles from the Wilde Irishe, the O’Byrnes and O’Tooles, who had been banished to the mountains. I somehow imagine them in checked shirts, ragged beards and jugs of hooch, with names like Zeke and Zeb, but that might be a later incarnation of the hillbilly tribes overlooking Wicklow’s Wonderful Coast.

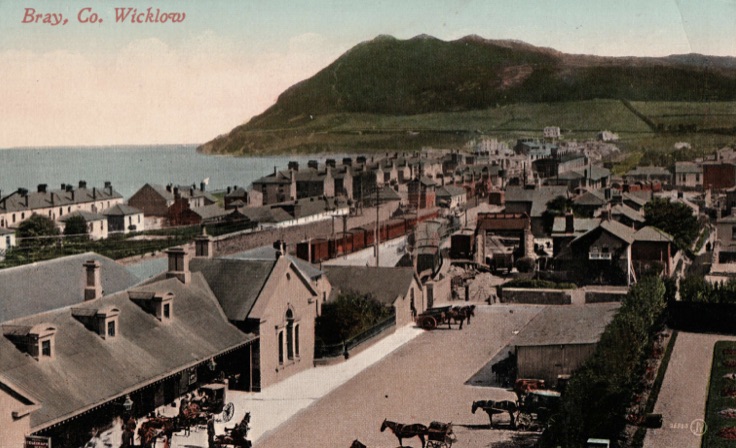

By the early nineteenth century Bray had developed from a small manor town into a sizeable industrial town with milling, brewing, distilling and lucrative inland fisheries. The first seeds of the seaside resort were sown in the Romantic era, as poets, painters, writers and philosophers extolled the virtues of the sea air and the spectacle of mountain scenery. Bray is rich in both.

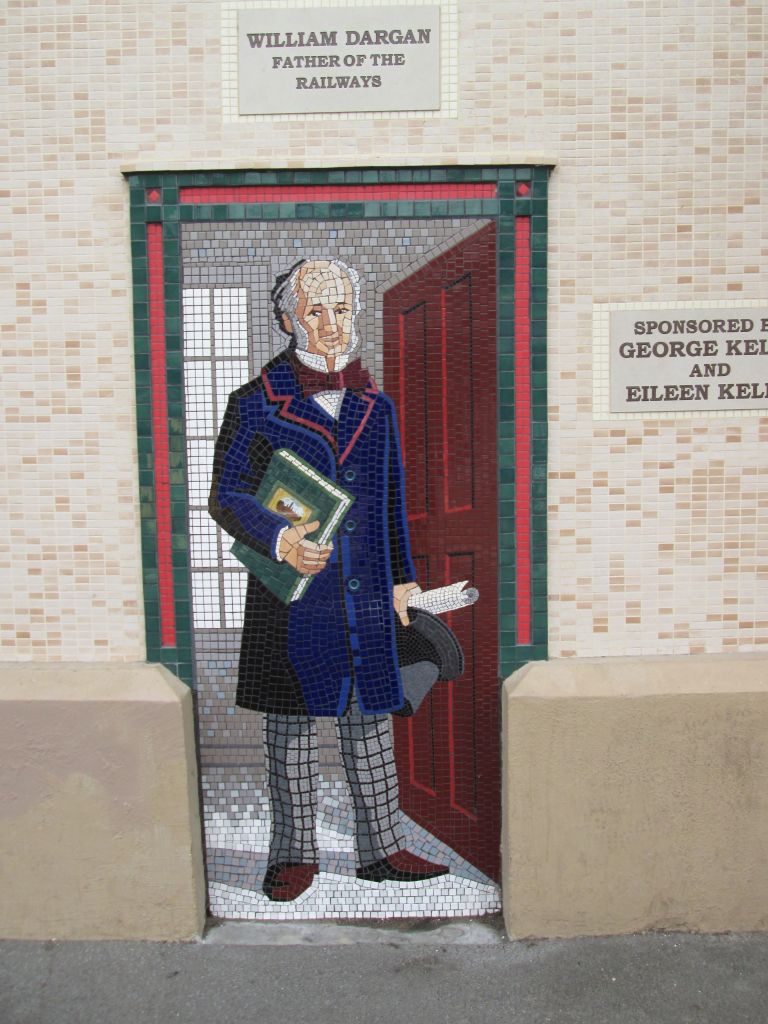

Dargan, having brought the railroad, established the seafront in its current form. The middle classes could make Bray their home and it became the fashionable resort in Victorian times, dubbed the Brighton of Ireland. After the war torn years of the early twentieth century, Bray went more downmarket. But the funfair still buzzed and the masses thrilled to dancehall sweethearts and rock n roll stars, dancing and romancing until the lights finally dimmed. Then, in the eighties, a new wave of migration from Dublin was greased by the coming of electric rail. Where would we be without DART?

Brays promenade is populated as much by locals as daytrippers and tourists. Bars and eateries with large sea facing terraces abound. Opposite the bandstand, a trio of long established premises are prominent. The Martello is a hotel and venue, home to Bray Arts soirees and music gigs. The original Porterhouse, with branches in Dublin, London and New York was next door, but in recent years changed ownership to become the Anchor. Jim Doyle’s is a renowned rugger pub. with goalposts at the gate and an elegant Jacobean facade. All serve food and segue into the wee small hours as night clubs.

The legacy of grander times endures. Victorian terraces line the seafront, top o the range residential and summer homes for the great and the good migrating from Dublin. Joseph Sheridan le Fanu stayed in the 1860s in a house with the Yeatsian name Innisfree. Lennox Robinson, dramatist, also lived here for a time. Robinson was manager of the Abbey Theatre for almost fifty years until his death in 1958. As Organising Librarian for the Carnegie Trust he was instrumental in founding Ireland’s public library service. Bray’s Carnegie Library, towards the old town, is part of that legacy.

Le Fanu grew up in Chapelizod, west of Dublin’s Phoenix Park, where his father was Church of Ireland rector. The House by the Churchyard is drawn from that environment. Written in the 1860s but set a century earlier, it is full of Le Fanu’s characteristic gloom with a plot that blends mystery and history. Le Fanu was later persuaded to set his stories in a more lucrative and British environment which he did with Uncle Silas. Using an earlier Irish based story Passage in the Secret History of an Irish Countess as template, it became his best known work. Le Fanu fell ill on completing the novel and came to Bray to recuperate. The bracing sea air was thought to be a boon. Le Fanu’s literary mind stayed focussed on darker things. His final collection, In a Glass Darkly, was published in 1872, a year before his death. It includes the novella, Carmilla. Carmilla, like Uncle Silas, has a first person female teenager narrator. She falls under the seductive spell of the eponymous Lesbian vampire. Both concept and execution made for a provocative mix in those days. The story influenced Bram Stoker’s Dracula, and anticipated the more erotic modern depictions of Vampirism. It was said he died of fright, implying that he was a man with a window to the supernatural. In fact, Le Fanu’s narratives were carefully ambivalent about the supernatural, maintaining the possibility of rational explanation. But they would make your hair stand up in fright.

Chanteuse Sinead O’Connor lives nearby. O’Connor was an early protege of U2’s Mother Records, making waves with her first album The Lion and the Cobra. Her version of Prince’s Nothing Compares 2U was a breakthrough hit for her in 1990.

I go out every night and sleep all day

since you took your love away

it’s been so lonely without you here

like a bird without a song

Never without a song, she has courted success, adulation and controversy ever since. A man I met in a bar told me his curiosity was piqued by a note pinned to her porch window. He snook up the drive to read it, squinting to decipher the small writing which demanded: Please do not peer into this window!

Farther on, the architecture blossoms into the extravaganza of the Esplanade Hotel. Built in the late nineteenth century, it is a three story red brick crowned by three conical turrets giving it the profile of an exotic chateau. Next door, the Strand Hotel, originally Elsinore, was owned by Oscar Wilde’s parents, Sir William, the renowned surgeon and Lady Jane. Jane, wrote under the pen name Speranza, and was a poet, folklorist and passionate advocate for Irish revolution and women’s rights. In the 1860s William was accused of molesting a female patient and Jane, leaping to his defence, became embroiled in a court case which she lost, incurring expenses but, tellingly, damages of only a farthing. When William died bankrupt Jane lived out the remainder of her life in poverty. She was buried in an unmarked grave in London

Oscar’s trials began with his inheritance of the property. Problems with the sale in 1878 resulted in a legal suit which was sorted in his favour, but he was stuck with costs. His more famous trial in the 90s saw him imprisoned for two years for gross indecency with other men. In literary terms it yielded the Ballad of Reading Gaol, which may have been influenced by his mother’s writing. She died while he was in prison.

I never saw a man who looked

With such a wistful eye

Upon that little tent of blue

Which prisoners call the sky,

And at every drifting cloud that went

With sails of silver by.

The Strand Hotel for a long time hosted Abraxas writers group, where I honed my skills alongside bridge clubs, poetry slams and Lions gigs, aye, with football on the telly and many’s the pint of beer. The Strand itself suffered unhappy demise some years back. Under new management, it is now known as Wilde’s.