Leaving Newcastle village behind, we can return to our coastal trail via Sea Road. South of Sea Road and not far from the beach, there’s public access to the East Coast Nature Reserve at Blackditch Wood operated by Birdwatch Ireland. The approach walk heads towards the beach then turns south along the landward side of the coastal ridge carrying the railway. The path heads back inland onto a boardwalk crossing a stretch of fenland through high reeds. There are eighty acres of preserved wetland to be explored and enjoyed.

The feral fen had all but vanished from this coast through drainage and modern development. It was nurtured back to health by the Birdwatch project about fifteen years ago, stemming from a European wide initiative at the start of the Millennium. Water levels were raised and encroaching woodland removed to restore the natural environment. Another aspect has been the introduction of diminutive Kerry Bog ponies whose grazing controls the vegetation. The fens, intertwined with wetland, willow scrub, and indigenous birch woodland forms a rare and precious environment.

There’s a treasure of birdlife here. Whooper swans and Greenland geese come south from the Arctic as do such predators as Peregrine falcons and harriers. The little egret’s a resident and you may spot kingfishers, curlews, herons and more. Birdwatch Ireland help the dedicated ornithologist with three observation hides in place. Boardwalks curve through the wetland making access easy for the wanderer without intruding on the visual integrity of the landscape. It’s like walking on water.

Following these paths is to step into another time and place. In summer heat I might wear a check shirt and hum a few Creedence numbers. In the shoulder season a spooky gothic feeling pervades. In winter it’s mostly out of bounds, and prone to flooding, which is its natural state. Making our instinctive way southwards, and there are signs, we make egress to the beach at Five Mile Point. We usually complete a loop walk returning north along the beach. It’s about a 7 kilometre round trip.

From 1856 you could hear the lonesome whistle blowing down the tracks. The line now ran all the way to Wexford extending from the Dublin – Bray connection two years earlier. Newcastle’s pleasant little railway station was built, a lonesome outpost for ninety years. Newcastle Station remained in operation until 1964, but unlike Kilcoole it was never reopened and is now a private residence. There are a couple of ruins along the line a few hundred yards south of the station. Here, where Ireland’s belly bulges toward Wales, this part of our coast, so isolated now, has been for millennia a bridge to the wider world. Adventurers put ashore and new connections were made. The Cable Hut, a neat redbrick ruin was the terminal for the first submarine telegraph cable laid from Nevin in Wales by Capt Robert Halpin in 1886.

Halpin was born at the Bridge Tavern in Wicklow Town in 1836. Hearing mariners’s tales in his father’s tavern made him determined for a seafaring life and he left home at ten to follow his star. By the age of twenty he’d sailed around the world and soon gained his first command. Aged twenty four his ship the Argo struck an iceberg off Newfoundland and sank. It was a setback for the young captain, but he recovered. A swashbuckling spell saw him running blockades in the American Civil War but it was the Great Eastern which made his name.

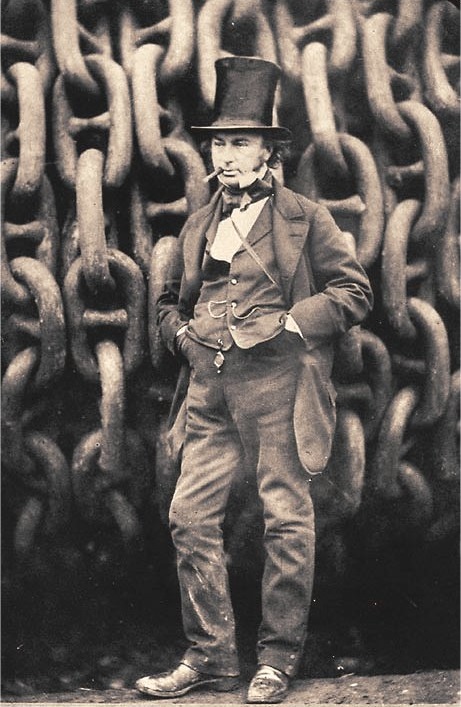

Launched in 1858 the great iron ship was five times larger than any other ship then built and was the brainchild of Isambard Kingdom Brunel. Jules Verne dubbed it the floating city, but it was something of a white elephant as a passenger liner. Passed from Billy to Jack, the ship was redeemed when pressed into service laying submarine telegraph cable. In 1866, the Great Eastern, with Halpin as first engineer, laid the first successful transatlantic cable to work uninterrupted, from Valentia in County Kerry to Hearts Content in Newfoundland (now Canada). As captain of the ship, Halpin was responsible for laying twenty six thousand miles of cable, enough to circle the globe, and earning him the nickname, Mister Cable.

Hey ‘chelle it’s about time you wrote

it’s been over two years y’know, my old friend

take me back to the days of the foreign telegram

and the all night rock and rolling

hey ‘chelle we wuz wild then

Halpin returned to live in Wicklow in 1875 and built Tinakilly House at Rathnew, two miles north of Wicklow Town on the other side of the Murrough. The house was designed by James Franklin Fuller, the Kerry architect responsible for such gothic masterpieces as Kylemore Abbey and Ashford Castle, as well as Dublin’s Farmleigh House and St Catherine’s church in Thomas Street.

Halpin died in 1894 aged just fifty eight. After such an adventurous life, his death was caused by a minor cut inflicted while trimming his toenails. He contracted gangrene and died. Tinakilly House now operates as a hotel with a renowned restaurant. The government likes to meet there, as do I. But not with them.

Hey ‘chelle you know it’s kind of funny

Texas always seemed so big

but you know you’re in the largest state in the union

when you’re anchored down in Anchorage

Karen Michelle Johnson, professionally known as Michelle Shocked, penned her signature song, Anchorage for her 1988 album Short, Sharp, Shocked. It wonderfully conveys distance and distant friendship, two contrasting spices of life. As birds migrate so we too travel and seek. The song namechecks two friends of Shocked, Jo Ann and Leroy Bingham, a Comanche and a Blackfeet Indian who moved to Alaska after their wedding. One of my favourite songs, it induced an urge to see the place. Eight years ago I did, and on the taxi in from the airport I was pleased to find the driver, a blow-in from the Lower 48, was called Leroy. And he said ‘hello’.

From Five Mile Point, you’ll notice the strand curving slightly to the right and the low bulk of Wicklow Head inserts itself across the southern horizon. We’re headed into port. Amongst other adventurers on this stretch of the Wicklow coast were Saint Patrick, patron saint of our isle. According to John Bagnell Bury, 1861 – 1925, Professor of Modern History at Trinity, Saint Patrick arrived on his mission to Ireland in the port of Wicklow at the mouth of the river Vartry. Bury figures Patrick had escaped his spell as a slave from here also. In ancient texts there is some confusion as to whether the river is the Vartry or the Dargle, which would see Patrick landing at Bray. Either way, he was not well received by whichever set of inhabitants first set eyes on him. Amongst his acolytes was a young priest who had his teeth knocked out by stone throwing locals. Since styled a saint, he bestows his name on the county; Cill Mantain in Irish. Mantan is a nickname meaning toothless or gummy. While Patrick got out of Dodge and took off for Skerries in North Dublin, Mantan stuck around to preach the gospel to the locals. Though with what clarity we can only wonder.